Volumes are to substances what space is to air. They are inert, homogeneous, devoid of qualities, and conceivable only in quantitative terms of length, breadth and height. No magic occurs in volumes because they equally support and deny every possibility. They are cartesian abstractions. Architectural representations of ‘places’ created by the leading digital tools tend to represent nothing more than these vacuous spaces.

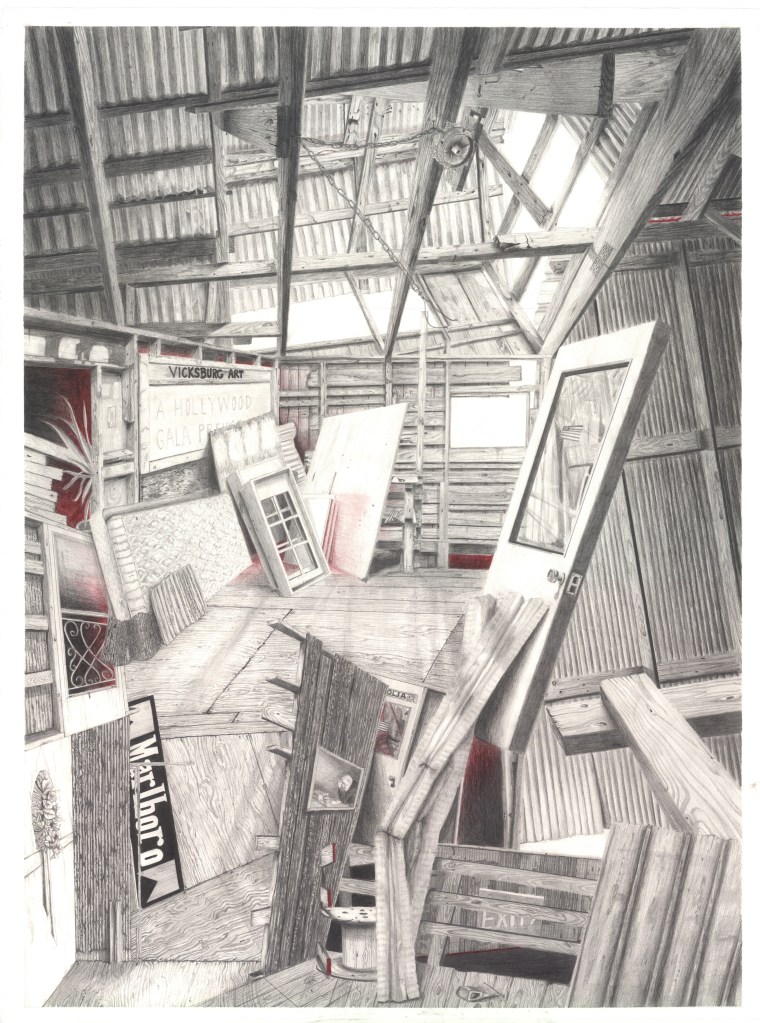

Substances, stuff-like as they are, are different. They are heterogeneous. They could be this or that or anything else but in each specific instance this one appears as this and that one as that. At each instantiation, a substance stands forth as one realized possibility, plausible or implausible, against the field of all possibilities.

Existence as a realized thing against the possibility of endless variation is critical to making and meaning and, perhaps, making meaning. As Gibson points out, substances vary in rigidity, viscosity, density, strength, elasticity, plasticity, and degree of light absorption, as well as susceptibility to chemicals, water, and air. This variation alone grants a qualitative world in or against which we have lives. These substances stay the same or change or both in the midst of a world filled with and affected by other things, including us, as we move through the medium of air. Most importantly, changes to substances and their resistance to change occur at scales we can see, hear, smell, taste and touch. They are, and are grounds for, environmental events.[i]

Judgements of plausibility, and ultimately meaning, are rooted in how closely a substance’s stability or its change in the environment matches our expectations and desires. Divergences from expectations and desires, regardless of whether the expectations or desires are for things to change or stay the same, become vectors of information first. We process this information, attempting to work it out. When we can’t, when we are unable to connect the environment as perceived and understood with an expectation or desire for what it should be, a sense of helplessness – in literary terms, a muthos – opens us to irony and feeds a burgeoning internal process of narrativizing experience. In other perhaps simpler words, when substances differ from expectations or desire, a story emerges.[ii] And stories are vehicles of meaning.

A step, however, is missing in this story. It is a step missing in most stories of architecture and architectural experience – particularly in recent fetishizations of material science: We don’t see substances as substances. No one does. With sufficient training we might understand their inner composition. We certainly can learn to conceive of substances and know their properties in particular environments. But what we perceive, or what we think we perceive if that is a different thing, are surfaces.

[i] Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, 16.

[ii] Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, Volume 2, 19.