Gibson expands on the ecological laws of surfaces by noting the range of grades or classifications into which every surface fits: luminous vs. illuminated, lighted vs. shaded, volumetric vs. flat, opaque vs. translucent or semitransparent, rough vs. smooth, glossy vs. matte, homogeneous vs. conglomerated, and hard vs. soft.[i] Everything an architect can do is circumscribed by these classifications and the ecological laws. Surfaces are the basic constituents of architecture – the primary building blocks of experience.

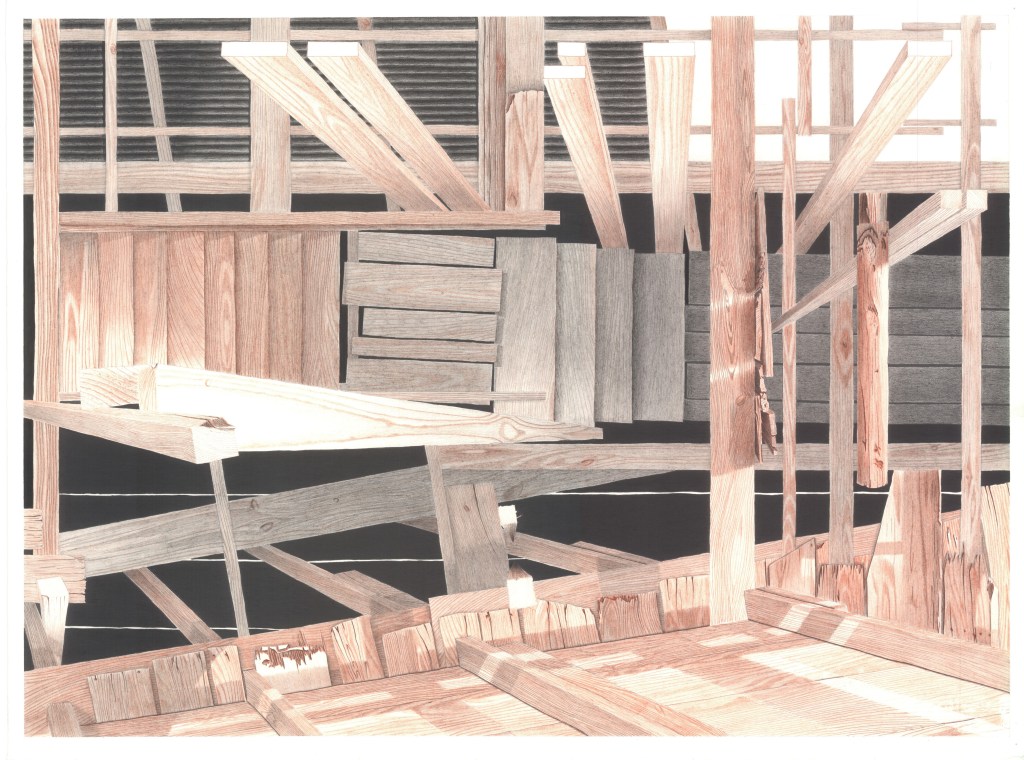

The image in meditation #25 Substances, not volumes, and here (see figure 6) are student attempts to capture the baroquely layered complexities of Earl’s Art Shop – folk artist Earl Simmons home/studio/gallery/juke joint outside Bovina, Mississippi – in a single drawing (figure 7 shows the front façade of the second incarnation of Simmons’ home no longer extant). These drawings avoid the emptiness of space and abstractness of volumes in space without falling into the trap of technological myopias (drawing details) or pragmatic resignation (floor plans and building sections). Both Kyle Stribling (figure 5) and Daniel Perschbacher (figure 6) render the spatial complexity and atmospheric quality of place via faces, edges, and vertices because these are the primary building blocks of experiences of surfaces.

This is where I expect to hear “yeah, but architecture …” with various predicate phrases attached. Architecture has to serve functions (however those are conceived) and meet codes (whichever are applicable) without negatively impacting the planet’s resilience (however that is measured). Perhaps architecture needs to solve the world’s problems (whatever that could possibly mean). Still, the thing itself, the object we call architecture, is nothing but surfaces with which people interact in the ways described above. Surfaces are the physical limits and reality of architecture.

Surfaces are ambivalent, of course. They have no inherent meaning. A brightly lit surface is just an illuminated surface. A shaded one is merely darker. How then do these simple building blocks let us know that they serve a function, or meet code, or are resilient or solve the world’s problems, or indeed are works of architecture and not mere buildings? In short, how do surfaces gain value or convey meaning? The next three posts will address this directly. First, however, I’ll address the question poetically or magically – as poetic and magical experiences are similar to those of architecture.

Paul Ricoeur, the great philosopher of narrative, observed, “a work may be closed with respect to its configuration and open with respect to the breakthrough it is capable of effecting on the reader’s world…. So it is not a paradox to say that a well-closed fiction opens an abyss in our world.”[ii] Value judgements and meanings emerge in attempts to bridge closed descriptions or simple observations and discrepant outcomes. Religious epiphanies, moments of awe or wonder, street magic and grand illusions operate via discrepancies – in other words, misalignments of givens or facts with results. As magician Darwin Ortiz notes, “the primary task in giving someone the experience of witnessing magic is to eliminate every other possible cause. If it can’t have been caused by anything else, it must be magic.”[iii] Architectural experiences operate in similar ways. Poets, like architects, invent mental worlds with language conventionalized to the point that almost all understand the words. Magicians, like architects, have only the physical world with which to create their illusions. Cards and saws and tanks of water are all surfaces. To be successful, poets and magicians must first understand the expectations that people bring to the reading or trick. From a common ground of expectations, endless reinforcements and subversions are possible.

[i] Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, 26.

[ii] Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, Volume 2, 20-21.

[iii] David Ortiz, Designing Miracles, (Oakland, CA: Magic Limited, 2006), 37.