“What we see is not depth as such but one thing behind another.”[i]

Gibson again. Here he pre-empts architectural phenomenologists’ disavowal of perspective as a model of visual perception. We don’t see space or distance but layers of surfaces, our movement occluding some and revealing others step by step. (Figure 6 in meditation #27 – These are the building blocks of experience – is again useful).

It’s difficult to recognize its profundity the quote – “not depth … but one thing behind another.” It is so obvious. Its commonsensical. And yet, conceiving visual[ii] perception as founded on the recognition of layers of surfaces instead of being inherently spatial resolves problems of communication, or information transmission, that are prerequisite for narrative. How, for instance, do we have a conversation that implicitly assumes a thing’s location or its attributes or explicitly debates the quality of a ‘space’? Or why is it the case that we seldom sidetrack into discussions of which space or where when we discuss things? Philosophers of perceptual common knowledge refer to these experiences as triadic ‘joint constellations’ and explain our lack of confusion in such cases as necessarily founded on the objects present.[iii]That is, surfaces provide a shared frame of reference for communication and their layering impacts the speed at which we come to agreement on the nature of that frame.

The sentence above is fundamental to the design of places. Surfaces provide a shared frame of reference for communication and their layering impacts the speed at which we come to agreement on the nature of that frame. Its import is deepened when we overlay its intricacies with the complexities of the human visual apparatus. Due to the mental processing required for perception, and the enormous energy demands of that processing, our fovea only registers high-resolution information from the setting or scene considered important. We see bits and pieces of surfaces, areas of overlap, in technicolor and vivid resolution. Almost everything else is blurred and seen in shades of gray – regardless of what our brain leads us to believe.[iv]

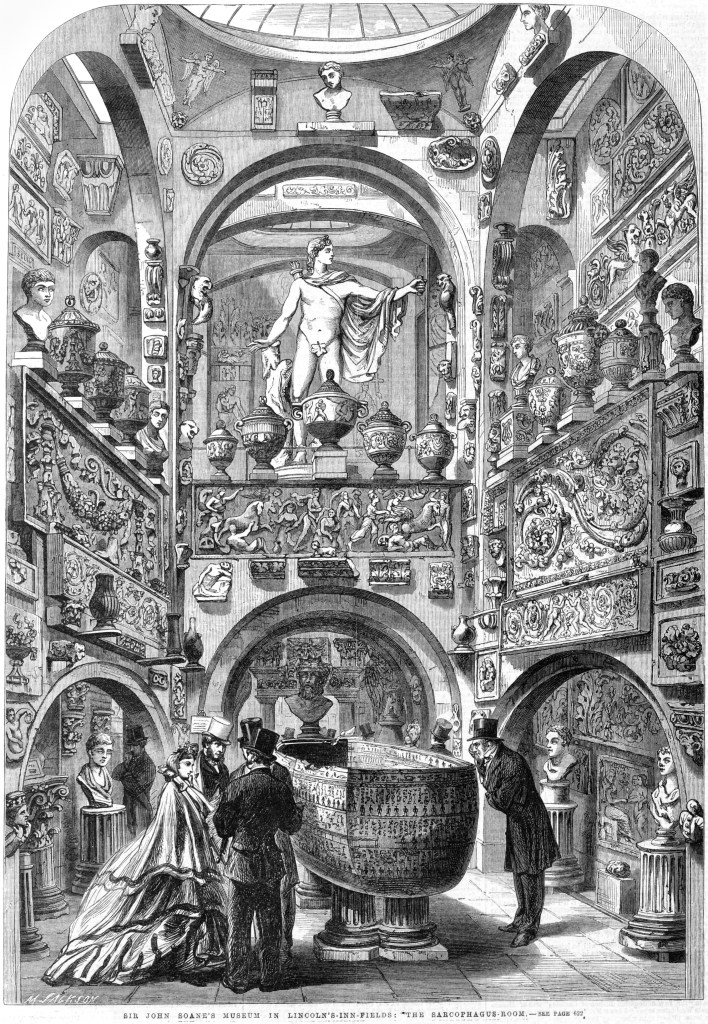

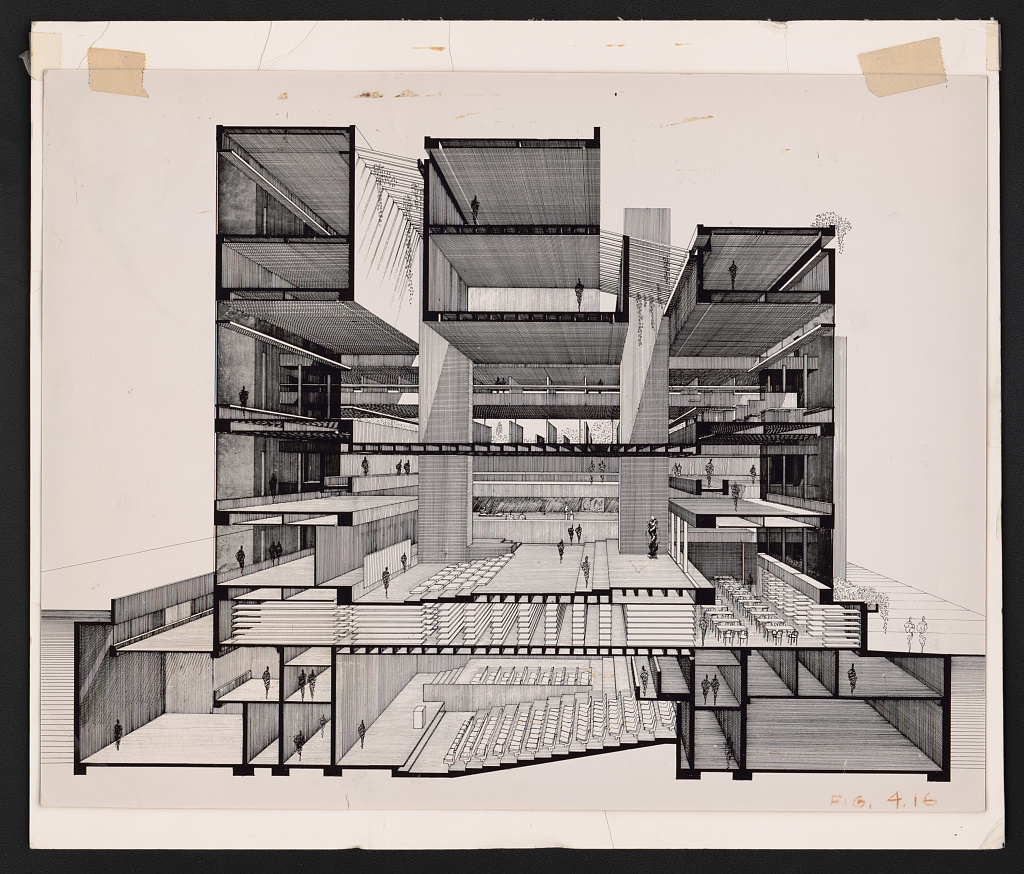

Reading the above slowly, it becomes apparent that perception isn’t so much spatial as temporal. Like narrative. Like meaning. A meaning-oriented approach to architecture is therefore novel-like – filled with layers and what could be called digressions. According to Calvino, “digression is a strategy for putting off the ending, a multiplying of time within the work, a perpetual evasion of flight.”[v] John Soane was a master of this approach in architecture (figure 8, above). As was Paul Rudolph (figure 9, below). While their works are often described as architecture of layered spaces, they are layered surfaces perceived as layered time. These are not works of volume but of tense.

[i] Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, 69.

[ii] The focus here is visual perception, as it is in Gibson’s work, and not perception broadly considered. Arguably, auditory, tactile, and even olfactory perceptions are equally important to architectural experience. That said, I believe a parallel analysis of sound, smell, and touch would reveal that occluded and revealed surfaces, not space, is key to understanding these other forms of perception as well.

[iii] Seeman, The Shared World, 70.

[iv] Kuhn, Experiencing the Impossible, 85-86, 88.

[v] Calvino, Six Memos for the Next Millennium, 46.