Before we can address how fiction-making animals’ encounters with works of composition make them protagonists by choreographing their movements, we must consider the autonomy of those animals. Architecture has a history of assuming a universal subject. ‘If I, the great (formalist, phenomenological, etc.) architect feel or understand a space in a particular way, all people (that matter to me) will experience the space similarly.’ No one literally says that but it’s a reasonable summation of an implicit assertion behind almost every architectural manifesto or treatise.

Elsewhere, I have called the result of this myopic worldview puppeteering – architects’ belief that they can and should dictate experiences to others – and argued that it is impossible and, even if it were possible, unethical.[i] How then is it possible, and to what extent is it appropriate, for works of composition to make our fellow humans feel like protagonists by choreographing their movements? How do we even understand the work as it will exist for others?

Questions surrounding ethics and the extent of experiential control appropriate to architecture are the primary topics for part three of these meditations: “Architecture as Material Fiction.” For the time being, I want to focus on the question of how. How, in short, do we inhabit architecture from another’s perspective? How do we design for people different from ourselves?

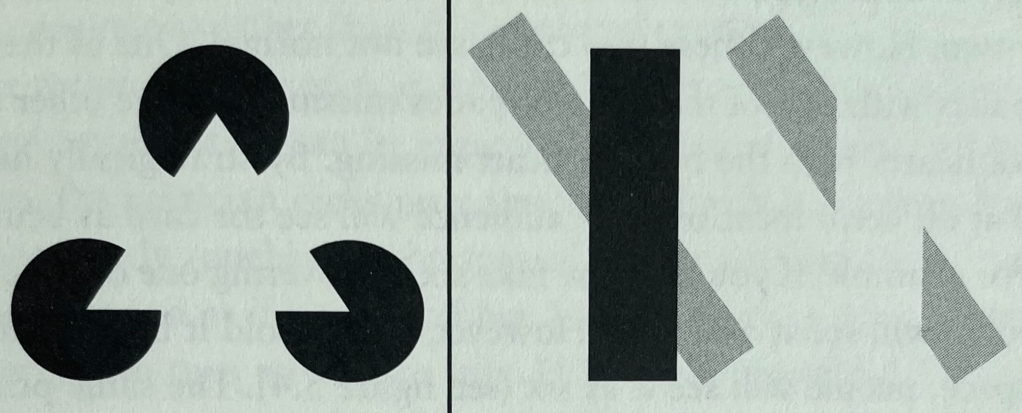

First, it is important to acknowledge the individual-social continuum that constitutes each individual, bridging personal biological autonomy with shared cultural constructs that make up our social being. Starting at the individual end is biology. For designers, the key feature at this end of the continuum is proprioception – the combined inputs of all the senses given a particular location and time exclusive to that subject. We can make informed guesses and attempt descriptions, but the specificities of personal emplacement are literally unsharable. From proprioception we move along the continuum to psychology and the evolutionarily acquired modes of perceiving the world. While these too are personal, the constellation of environmental psychological attunements are consistent enough to have been systematized, tested across cultures, and codified. Gestalt grouping principles, such as the law of closure and the law of continuation (see figure), are examples of this.[ii] And from psychology we move to sociology to discover the meanings of place and culture that are learned, consciously or not, from cohort, tribe, etc.

This continuum can be rendered in terms of the spectrum of objects perceived: from the subjective objects (Gibson’s term for the appearance of our own bodies in perception) to symbols. All of these objects are representational to the extent they are perceived and understood. And all are perceived using the same sensory systems. That said, the latter, symbolic objects, possess representational content greater than the mere mechanics of biology and material science. Symbols differ from subjective objects in that they are representational through and through. “This is merely to say that a representation is a social construct, with historical (even biological) roots – like any idea – and that the spirit that inhabits the imagination is not necessarily a figment created by the person who ‘has’ that imagination.”[iii]

The initial answer to questions about designing for individuals very different from us is rather obvious: design for the aspects of humanity that are shared. Returning to the thread: How does an encounter with a work of composition make us more fully narrators, thus centering fiction-making animals as protagonists, without assuming a universal subject? By privileging symbolic objects and representations on the sociological end of the spectrum. Subjective objects and proprioception will take care of themselves and differ person to person. If we plan the social aspects correctly, however, fiction-making animals will be immersed in representational content. Symbols, with their reliance on history, drag us toward an awareness of time. This awareness doesn’t make us protagonists, per se, but it positions us to take that leap.

[i] Callender, Architecture History and Theory in Reverse, 39-50.

[ii] Kuhn, Experiencing the Impossible, 111.

[iii] Peterson, Maps of Meaning,154.