First, a note in praise of vagueness. Why do many architects insist not only that works of architecture be generated with specific ideas in mind but that the public understand those ideas in equally specific ways? I am not questioning the value of the former. Nor do I want to imply that the public reception of works of architecture doesn’t or shouldn’t matter. One reason I went to art school instead of furthering my architectural education was the insularity verging on elitism of the discipline. My sense then (and now) was that architectural ideas that are visible/detectable/meaningful almost exclusively to other architects (and often only a small subset of them) don’t constitute meaningful pursuits. Of course, my education in painting and sculpture left me painfully aware that art of the 20th and 21st century suffers the same insularity. But I have consoled myself with the knowledge that the Artworld is something people can participate in by choice, more or less. People mostly self-select to go to galleries and museums. Architecture, as a very (I would say forcibly) public art, cannot afford to be so cavalier if we are going to talk about issues of diversity, inclusivity, sustainability, or the public good. Italo Calvino’s praise of Giacomo Leopardi’s use of exactitude in the service of vagueness is an important corrective in this regard.

Second, a note on the uses of vagueness. There is an implicit, though seldom stated, belief in many cultures that empirical objects have singular identities while the works of nature have no set meaning and are therefore more open to interpretation. And, at first blush, Calvino seems to share this belief when he quotes Giacomo Leopardi’s Zibaldone about the joys of moving through nature.

“Contributing to this pleasure is the variety, the uncertainty, the not-seeing-everything, and therefore being able to walk abroad using the imagination in regard to what one does not see. … the pleasure of variety and uncertainty is greater than that of apparent infinity and immense uniformity.”[i]

Giacomo Leopardi

On second reading, however, it is obvious that a human made environment could offer variety, uncertainty, etc. in similar ways. And on a third reading of the whole passage, it becomes clear that Leopardi as well as Calvino are interested less in nature itself than in the ability of literature to afford the experience of exalted vagueness that nature alone supposedly offers.

Third, a note on Gibson, nature, and affordances. J.J. Gibson has little patience for distinctions of artificial or cultural environments as opposed to natural ones. Instead, he coined the term affordance to capture “the complementarity of the animal and the environment…measured relative to the animal…in a sense objective, real, and physical…[that] points both ways, to the environment and to the observer.”[ii] Things like surfaces conducive to sleeping or sitting on or sleeping or sitting under in inclement weather are examples of affordances. Whether those surfaces are supplied by nature or human effort does not alter the fact that they provide a niche for the preservation and possible enhancement of our lives.

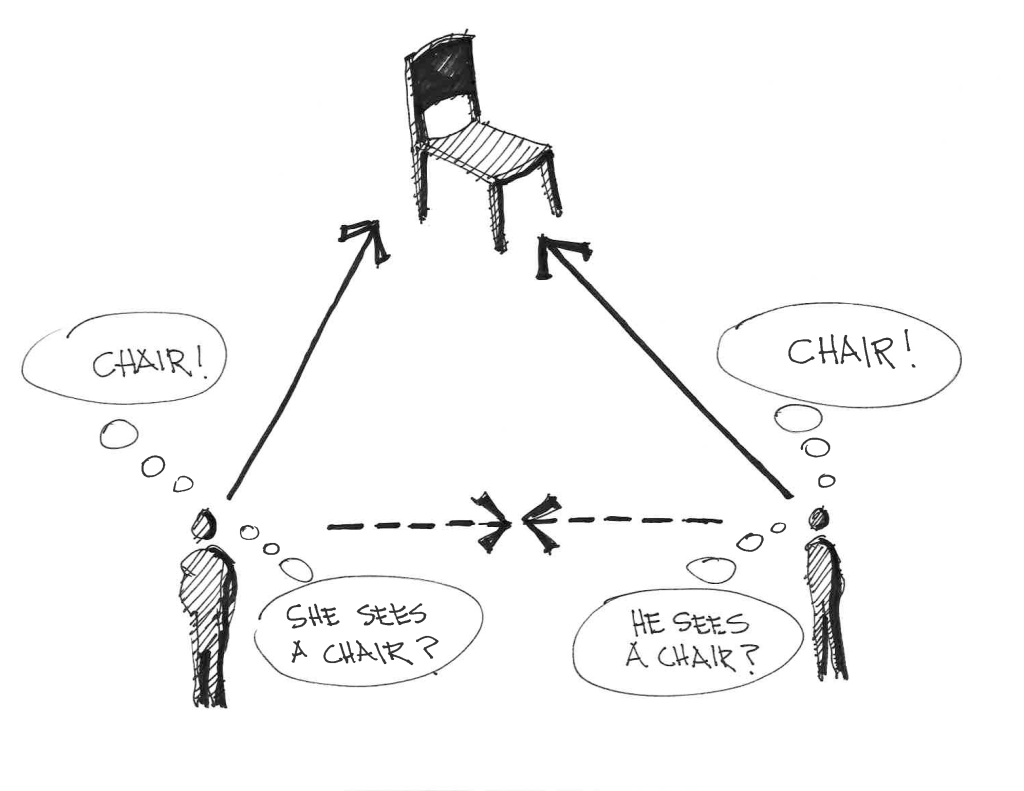

Fourth, a note on affordances and knowledge. Affordances, understood as complementarities of animals and environment relative to the animals, provide some foundation for a theory of shared or social knowledge. Here I am specifically thinking of philosopher Donald Davidson. At the heart of Davidson’s conception of knowledge, which acknowledges “membership in a society of minds,” is his notion of triangulation: we must know others’ thoughts to know our own, we must know our own thoughts to evaluate others’ thoughts, and we must share a world and its values to evaluate each other. All three aspects are required or shared common knowledge is impossible. The connections from ourselves to the world as well as from others to the world are rooted in affordances (see figure 13). And like Gibson’s theory of affordances, Davidson’s three-part theory of knowledge eschews objective-subjective or quantitative-qualitative dilemmas.[iii]

Fifth, a note on what affordances mean for our understanding of experience. Understanding the world as triangulated affordances tells us that our commonsense notions of the world and its order are backwards. We tend, for example, to believe that settings pre-exist the events that happen there. In Gibson-like language, we tend to believe affordances exist and animals subsequently wander into them. We tend, for another example, to believe that relational judgements like too high or too low or too firm or too soft are idiosyncratic valuations in the eyes or skin and mind of the beholder. That is, we tend to believe affordances pre-exist animals’ judgements and are thereby immune as any object is immune to subjective perceptions. These notions are pervasive, and incorrect.

The world, teeming with events, becomes setting when an affordance is made. It rains – at that moment the rock outcropping or sheet metal overhang becomes a shelter for sitting or sleeping. The animal gets tired – at that moment the rock or stack of wood becomes a bed or chair. Affordances point both ways, as noted above. Settings and even times evolve with and through the affordances we make. And from this perspective, Paul Ricoeur’s comments on the blurred boundaries of subject and object in narrative time take on new force:

“Like Braudel the historian, we must not speak of time as being simply long or short, but as rapid or slow. The distinction between ‘scenes’ and ‘transitions,’ or ‘intermediary episodes,’ is also not strictly quantitative. The effects of slowness or of rapidity, of briefness or of being long and drawn out are at the borderline of the quantitative and the qualitative.”[iv]

Paul Ricoeur

[i] Calvino, Six Memos for the Next Millennium, 62.

[ii] Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, 119-121.

[iii] Donald Davidson, Subjective, Intersubjective, Objective, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2009), 220.

[iv] Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, Volume 2, 79-80.